Culture

Reviews: Cable Girls (Las Chicas del Cable)

Published

7 ans agoon

[simplicity-save-for-later]

Language: Spanish (Spanish dialect)

Type: Period Drama

Plot:

Fate brings four girls, with different backgrounds together as an instance of luck turns into a tumultuous yet strong friendship.

The show is also about a feminist dystopia that details the struggle of Spanish women in the early years of the 20th century, while exploring other themes including: sexuality, morality, psychology and star crossed lovers.

Why this show?

This show is set in the 1920s, back when our current ongoing state of patriarchy was far more disparaging toward women. In fact, the laws in Spain were men made and men serving. Women had no right to divorce, to ask for the custody of their children if marriage annulment was obtained, their wage gap equaled half men’s salaries and they weren’t able to extract money from banks without their husbands’ written and signed consent. And the list goes on and on…

Perhaps, researching the term « Herstory » would be necessary in order to understand the true depth of this show. It sets focus on women whose merits get cut short solely for the sake of being women.

This is particularly discussed on the second season as Lidia’s character rises to power yet lingers in the background, overshadowed by her male coworker who gets the praise for presenting the work she actually accomplished.

It also answers the question I, myself, have thought about as a child « Why are most inventors and creators men and not women? »

Why is Einstein universally acclaimed but not his first wife Mileva, who was equally genius and one of the greatest scientific minds of her generation? To make it worse, she remains practically unknown and uncredited for both her intellectual abilitities in the scientific field and her collaborative work with Einstein, that ended up cheating on her and remarrying later.

There’s also Mary Shelley, the author of the infamous Frankenstein. To this day, her memory still suffers from the unwarranted insistence of skeptics who question her authorship of the book, mainly because her husband, Percy Shelly, was a famous writer and poet himself.

Speaking of the second season, we will get to see a scene straight out of a Susan Glaspell’s « Trifles » (shout out to Miss Aycha!) which combines both my serial killer inclination and my inner feminism together, and that probably unleashed a debate over violence and justice, somewhere.

That’s it, I shall spoil no more.

That being said, I’m not here to carry out a feminist agenda nor to use revolutionary subliminal manipulation techniques so let’s move on to a different point.

Beyond the boundaries and limitations set by the canons of decades-long oppression, and silent obedience come the other aspects of « Cable Girls ».

Each episode is followed or initiated with a morality and is centered around an emotion or a concept including loneliness, fear, love, death, luck, vengeance, regret etc..

Besides that, it also focuses on several other taboo subjects and issues Spain dealt with in that period of time, such as the unconventional treatment (more like « torture methods ») of what was deemed as « behavioral deviancy » and the characters’ concerted efforts to change those practices. To put it in simpler wording, « the queer community suffered a lot. »

It is, as well, a tale of friendship with an interesting character arc. For example, we will witness the switch of Carlos’s character from a nonchalant and irresponsible guy squandering his family’s wealth to a far more mature yet damaged person.Or Angeles who will upgrade from her initial downtrodden and submissive state to an independent self-sufficient woman who’s brave enough to regain control over her life on her own.

Finally, and to prove there are exceptions to every rule, Carlos & Miguel’s characters were feminists themselves, especially Miguel, whose tolerance, open mindedness and respect for women proved that not all men back then were inherently « bad », and that their actions weren’t necessarily the product of social constructions enforced on them they had to abide by but rather their own free will and chauvinism.

Favorite Character:

Francisco is every woman’s dream guy, basically. (And I’m not just talking about his physical looks) (or am I?) (I’m not, but I should)

In this extremely volatile love triangle, I feel like he wasn’t given his due for all the sacrifices he’s made -and he possibly never will.

Imagine running away with the love of your life, losing them that same day then discovering they fell in love with your best friend around the time you reunite with them again, 10 years later.

Although, I’m not particularly bitter about Carlos’s character (the other end of the love triangle) I still feel like Francisco deserves Lidia. He’s the embodiment and the prime example of unconditional love and selflessness. His inner struggle to do the right thing by his loved ones incessantly pushes him to repress his own desires and longings by constantly prioritizing theirs over his, hence adjusting his own life around those he cares about -not the other way around.

What I didn’t like about this show:

Though no major event was left unexplained, some details were ignored or left to interpretation, creating a minor plot hole in the storyline that could’ve been easily avoided.

Something else I felt the need to comment about was the choice of music. Contemporary American pop music shouldn’t be the kind of music used on a historical Spanish drama. It even makes you uncomfortable and slightly out of place, at times.

Lastly, though I love me some Francisco, his character was way too sugarcoated and unrealistically painted. No one can possibly -nor should- be that loving and self sacrificial. It even gets annoying at times.

Critics:

Rotten Tomatoes: 90%

IMDb: 7.8/10

Common Sense Media: 4/5

Articles similaires

You may like

Culture

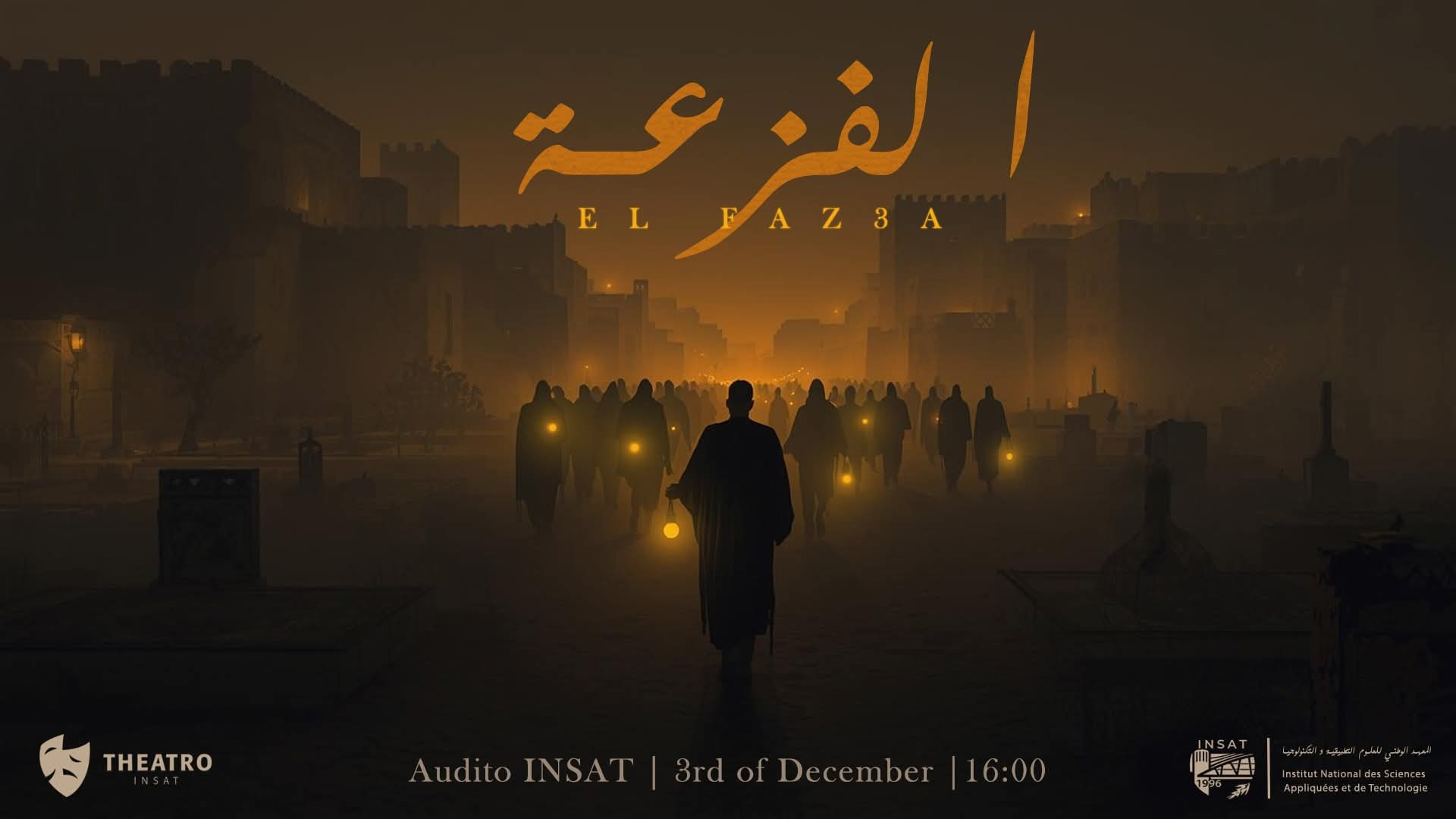

الفزعة: صرخة مسرحية تكشف ما يخشاه الصمت

Published

3 mois agoon

7 décembre 2025 [simplicity-save-for-later]

ألج الغرفة بنار من الفضول تتوهّج في داخلي، فتحرق ضلوعي. يداعب وجهي دخان ثقيل؛ أهو دخان الغموض المكتوم، أو الفقد المحتوم، أو الفناء المنبوذ؟ أهو خلاصة الغضب المكبوت، أو الحزن المأثور، أم الهدوء المنشود؟

أجلس بعيون شاخصة في مقعد كدت أستعذب راحته لولا طواف أجساد بدت ساكنة رغم خطواتها المترددة، أو ربما هي ساكنة في واقع غير الذي نعيشه. كانت شبيهة بأشباح كُسيت ثياباً سوداء؛ لعلها رمز الخوف، بل هي رمز الحداد… أو لعلها ظلّ السلطة، تطوف بلا هوادة على درجات القاعة الظلماء، تحمل ضوءاً أبيض خللته لوهلة الحقيقة في ثوبها الناصع.ء

نطقت « الأشباح » لفظاً واحداً: « يا نبيل ». هنا أكاد أجزم بأنها تبحث عن فقيد. ظلّت الأجساد تدور، متفرّسة في الوجوه. خطواتهم تعبث بأوتار العود فتبعث موسيقى توحي بالتوتر بقدر ما توحي بالتفتيش المُلحّ اليائس. الجو مشحون بموجة من الارتباك، فأجدني لا أنصت إلا لصدى صراخهم. أكاد أنتفض من مكاني فأصرخ معهم: « يا نبيل، يا نبيل اخرج، علّك تريح هذه الأرواح المفزوعة المعذّبة ».ء

بدأت الأضواء تتجمع في قلب الركح، كأنها تريد أن تصرخ معلنة أن ما يجمعها همّ واحد وهدف موحَّد، على ثلاث مستويات، فإذا بهم مدرّج ينحدر بنا نحو الحقيقة. « شبيكم نسيتوها؟ » تنطلق الجوقة في التقريع والتأنيب، وتمحو الغموض عن قرية هي الجنّة المنسية المتروكة، وتعرّفنا بخصال سكانها البسطاء على أنغام « l’amour est un oiseau rebelle ».

وبمقطع موسيقي راقص، تناثرت مشاعر التوتر لتحل محلها بهجة تلاعبت بها درجات الأضواء الصفراء. وهنا نشدّ الرحال لنكشف الستار عن مكنونات هذه الشخصيات التي بدت من خلال أزيائها وحركاتها وطباعها المختلفة والمشوقة.ء

يتقدّم نبيل في هذه المسرحية بصفته اسماً اختير بعناية ملحوظة، إذ تتجسد فيه قيم النبل والبذل وتتجذّر داخله مشاعر المحبة الصادقة والإخلاص. فهو الطبيب الذي حاول جاهداً أن يكون صورة المثالية: صبوراً، إنسانياً، عطوفاً، صوتاً للمصلحة العامة والمنفعة الشاملة. غير أن هذا النبل نفسه كان نقطة ضعفه، إذ خضع في لحظات عدة لوسوسات المشاعر وهفوات العواطف، خاصة تجاه أسرته التي أحبها حباً شديداً، فكان انسياقه وراء أحاسيسه سبباً في النهاية المأساوية التي لقيها.ء

وقد بدا جلياً منذ بداية المسرحية حين فضّل مساندة شقيقه علي، متغافلاً عن الخطر الذي يمثله منتجعه، فدفع ثمن هذا التجاهل غالياً. وأكثر ما رسّخ صورته في الذهن سترته البيضاء التي لم يتخلّ عنها حتى برفقة أسرته، كأنها رمز دائم للوفاء والصدق وتذكرة بأن مصلحة الجميع مسؤوليته. ء

وعلى طرف النقيض يقف علي، أخ الطبيب؛ الرجل المهمش المتقلب الذي يشكّل، في ذاته، جملة من المشاكل الاجتماعية والانهيارات النفسية. رغم محاولاته البائسة لإثبات وجوده، فإن استخفاف الجميع به وتجاهلهم زرع داخله شعوراً مريراً بالاستنقاص والاحتقار. وما إن حقق نجاحاً بسيطاً حتى تحول هذا النجاح إلى الشعلة التي غذّت داخله رغبة عمياء في الانتقام؛ فأصبح المنتجع وسيلته لنيل رضا الناس واهتمامهم، لا لأجل منفعة حقيقية، بل ليعوّض سنوات النبذ والنسيان والانكسار.كان يدرك تماماً حجم الأذى الذي يتسبب فيه للأرواح البريئة، لكنه كان يرضي ضميره المتألم بتبريرات واهية من قبيل أنه « يخدّم في برشا ناس ». في تلك اللحظة يتجسد علي كتجسيد رمزي للشركات التي تحتكر الأسواق التونسية وترهب الدولة لمجرد أنها تشغّل الآلاف. ومع السلطة التي حازها، صار يحكم فلا ينصف، ويأمر فلا يعدل. الثروة والجاه أعمياه عن قيمة الإنسان، وعن قيمة أسرته، وعن حقيقة نفسه؛ فكان جبنه وخوفه مخفيَّين خلف حجاب من المكر والتحيّل. وعن طريق المداهنة والتصنع استغلّ مشاعر الآخرين و نبلهم. أما علاقته بنبيل فكانت علاقة قائمة على النفور والغيرة القاتلة المتجذرة في ذكرياته، وقد برز ذلك عبر أضواء الركح التي فصلتهما إلى حلقتين متباعدتين من النور، مجسّدة في جوهرها قصة قابيل وهابيل: أخ يغدر بأخيه الذي مدّ له يد العون، فتطاله لعنة الندم والانهيار إلى الأبد… دلالة على هشاشة الملهيات المادية أمام صلابة الروابط الإنسانية. ء

هذا النزاع الملحمي كان قابلاً أن يُمحى بتدخل شخص واحد، هو الترياق السحري الذي يشيد جسراً سرمدياً بين نبيل وعلي: للا البية. بدل أن تكون البرد والسلام الذي يطفئ نار ابنها الأكبر المستعرة، كانت سبباً في أن تزيد الطين بلّة وتوسع دون قصد الهوّة بين ولديها. رغم ما مرت به من صعوبات، إلا أن دروس الحياة لم تكن كافية لتغييرها؛ فهي التي عاشت على الكفاف مع زوجها الأول، لم ترضَ بسوسن زوجة لابنها، فرفضتها بقسوة واحتقار وتجاهلت مشاعرها. ء

للا البية كالغيمة السوداء التي تدرّ غيثاً نافعاً ولكنها تحجب الشمس؛ فهي تُعنى بأبنائها، لكن كتمها الدائم وعدم تواصلها الفاعل معهم خلقا جواً من البغض والكراهية. وما هذا إلا نتاج غياب الإحاطة اللازمة والمساندة النفسية المطلوبة منها. كونها أماً، كانت قادرة على السيطرة على الوضع منذ البداية، لكن تأنيب الضمير الذي يقضّ مضجعها تجاه ابنها الأكبر كان المانع الوحيد. ء

من قلب الظلام والعتمة يبرز نور الأمل؛ من صميم عالم تحكمه الشرور يختفي الخير في خيال سوسن. شخصية قوية بمبادئها، قيمها أعظم وأجل من أن تدهسها الأطماع رغم المغريات. هذا الملاك الطاهر لم يتخلّ لحظة عن أخلاقه وتمسك بأسرته، لكنه وُظّف بالتوازي لنقد الطباع الأزلية الطريفة التي تلازم المرأة: النميمة والفضول المفرط. ء

حول هذين الأخوين تتحرك بقية الشخصيات في دوائر متشابكة. نبيلة، زوجة نبيل، تمثل الوجه الآخر لنجاة؛ فكلاهما وجهان لعملة واحدة اسمها: المادة. نبيلة، بقلب قاسٍ ميت وروح داكنة لم تعرف الحب يوماً، اعترفت بأنها لم تُحب نبيل قط، وأنها رضيت بالزواج منه فقط لأنه طبيب مثقف ذو مكانة. هذا الموقف يلخص كل شيء فيها: محتقرة، أنانية، مستغلة، لا ترى الناس بجوهرهم بل بمظاهرهم. المفارقة أنها معلمة تنشئ أجيالاً؛ وكأن في شخصيتها نقداً عميقاً لواقع يصير فيه المربي متغطرساً يرى قيمته فيما يجمعه من مال لا فيما يزرعه من قيم. ء

إلى جانبها ترتسم نجاة كامرأة مادية، لا ترى قيمتها إلا في زينتها وجمالها. صورة صارخة لغريزة أنثوية تعيش في تحدٍّ دائم مع الأخريات. طوال العرض تحاول مجاراة نبيلة، وقد جعلت من سعادتها رهينة تجاوز نموذج وضعته هي معياراً للنجاح. هوسها بالجمال أنساها الأخلاق، فقبلت بالمنتجع رغم معرفتها بالخطر، فبدت كمن يسير خلف البريق ناسياً الحقيقة المظلمة خلفه. ء

يقف خلف نجاة بروز صطورة، أو إن صحّ القول: الضحية الأولى لأنانية نجاة العمياء. هو باختصار صورة تقليدية للرجل الذي يسعى في جهد جهيد لإرضاء زوجة لا ترضى. علاقته بزوجته مثال مصغر لعائلة تونسية، عوض تكوين جو عائلي دافئ تخلق محيطاً من التنافر والتباعد، وهذا ما ينعكس تماماً في الطباع التي ينقلها الأبناء. فمنير، الذي في ظل غياب التأطير والإحاطة، صار نموذجاً حياً للمشاكسة والاختلال. ء

هذه العلاقة الزوجية الفاترة قائمة على ثنائية: الطلب الملح المتواصل، وتحقيق الطلب، وإن كان لا منطقياً، مستحيلاً. ء

ما شد انتباهي أيضاً أن هذا الدور، رغم غايته الكوميدية، رسم بإتقان ملامح الرجل التونسي النمطي. فصطورة، الذي يرى في داخله أنه عاجز عن إرضاء زوجته، يتجه بلا تردد إلى إخفاء هذا العجز بالتودد والتقرب من غيرها من النساء، فكأنه يسعى للبحث عن قيمته في مكان غير مكانها. فحقيقته حتماً تنبع من داخله لا من رضا الناس. ء

النقص الذي يعيشه صطورة يتحول لا إرادياً إلى تعنيف متواصل، برز خاصة في علاقته بخنيفس؛ شاب رغم سذاجته يحمل طموحاً. بغض النظر عن محاولاته البائسة في أن يكون فاعلاً، إلا أن استخفاف الجميع به يخلق في داخله نوعاً من الاستنقاص والاحتقار لذاته، فيبقى بذلك عاجزاً عن تحقيق وجوده وماهيته. كان حضوره طريفاً، تماماً كحضور رجب الذي يخفي داخله جانباً مكسوراً. بضحكاته هو قادر على تزييف قناع من القوة والمسؤولية، يتفانى في تصميمه مستعيناً بنزعته الكوميدية التي باتت أكبر برهان على وحدته التي تضعفه وخوفه الذي يخفيه. ء

رجب تجسيد آخر للبعد المادي في المجتمع؛ كيف لا وهو يعنى بسيارته وعنايته بزوجته، وهذا دليل قاطع على قيمة « الميكانيك » على حد تعبيره، والأولوية الكبرى التي يوليها له. يختفي رجب ليترك الأضواء للزربوط. شدّني هذا الدور بشدة؛ فالزربوط بدا فكاهياً من درجة رفيعة، لكنه في ذات الحين وثّق بامتياز ثلاثة خصال في شبابنا: الجهل، التكاسل، والانحراف. ء

الزربوط، الذي يجهل المغرب، بل لا يكتفي بجهلها ويتعرف عليها على أنها « بلاد الشيخة »، جسّد بامتياز التيه والضياع الذي يعانيه الشباب التونسي. رغم أنه يتظاهر بالتجارة والعمل، إلا أنه يرفض قبول عرض صطورة المغري، ويرضى بمصدر رزقه اللامضمون بخلاً وتعنتاً. ملابسه تصديق لطباعه؛ فهو يرتدي رداء نوم يخفي فيه أغراضاً لا معنى لها يبيعها. ء

كان الحضور الشبابي واضحاً كذلك بظهور حفّار القبور، الذي يعكس تطبيقاً فعلياً للاستنزاف واللاإنسانية. فالإنسان يفقد قيمته حتى وهو جثة هامدة جامدة؛ جثث تُسلب ممتلكاتها قبل أن تُدفن، في قبور تُحجز لمن يدفع أكثر. أي على الأصح: إن لم تتصدر قائمة الواهبين الأثرياء، فلا مكان لك حتى بين الأموات. اسمه يوحي بدناءته وطمعه؛ فهو يسلب الموت حرمته ونواميسه، بل ويتمادى في انتهاك حدوده وقوانينه. لذا، بلا شك، كان المنتجع بالنسبة له استثماراً هاماً في سوق الأموات، يتزايد من خلاله الإقبال على المقابر والطلب على المدافن. ء

أمام الخطر الداهم الذي بات يهدد راحتها، انتفضت الشخصيات واتحدت للتخلص من المنتجع. لكن كلمة واحدة من العمدة كانت كفيلة بأن تثني عزائمهم. من خلال هذا المشهد يبرز نجيب وسماح، صحفيان يتزاحمان لسرقة الأضواء. ء

بدت سماح مرآة تعطي بتفانٍ اللامسؤولية وغياب الاحترافية؛ الصحافة بالنسبة لها مورد رزق ومجال للتعبير والترويح عن الذات. بكل عفوية تبث للمتقبل مواضيع لا معنى لها، ثرثرة مشتتة تلهي ولا تنفع. ء

أما نجيب، فالصحافة عنده تفقد مصداقيتها ونبلها، فيصبح هدفها الأسمى ومسؤوليتها الأولى: إخراس أصوات الحرية، وإبادة المعارضة والرفض. قد تبدو عليه احترافية، لكنها زائفة؛ بلا أساس. الشفافية والصدق قوام الصحفي وروح علاقته بالشعب. بغيابهما يغدو مداهناً متملقاً، ضبعاً ينتظر بقايا الأسود حتى يعيش. لذا، يعتبر نجيب نقداً صريحاً ومباشراً لواقعنا الذي نعيشه: لا صحافة تمثلنا ولا إعلام ينصفنا. ما شدني أيضاً هو الأساليب التي يوظفها نجيب لإخفاء الحقائق: اختيار متكلم بعينه ليمثل المظاهرة، وتشتيت المتقبل بالانتقال من المشاكل الحقيقية لمواضيع أخرى تافهة لا شأن لها بالمصلحة العامة. ليس إلا تلاعباً بالشعب وإلهاءً مستفزاً ومسكناً لردات أفعاله وأفكاره. ء

آخر الشخصيات ظهوراً أشدّها وطأة: رباعي الاستبداد، الذي يمثل دائرة سجنت في داخلها أرواحاً معذبة، محطمة، لا شفاء لدائها، وأنّى لجراح القهر أن تندمل؟

ينطلق الإعصار الدائر المنتفض من دليلة، امرأة رضيت أن تُنعت بالجنون وما هي بمجنونة، ولكنها جعلت من الجنون وسيلة لنحت عالم تكون فيه الأحلام كالأوهام، والأحزان كالأشباح. أمّ فجعت بفقد ابنيها، حُرمت حتى من رثائهما وبكائهما. تحت وقع الصدمة لم تتقبل الواقع، وفرّت نحو عالمها الخاص، حيث يجتمع شملها بأبنائها رغم مسحة الجنون التي تتخفى خلفها. بدت الأكثر تعقلاً، فعلى لسانها اعتنقت الحقيقة: « الفلوس وسخ الدنيا يا عمدة ». كلمة ظلت تكررها كأنها تحذر علياً من الوقوع في هوّة الجشع. ء

يواصل الإعصار الدوران فيبرز فتى مكبل مظلوم. القضاء عماد الدولة؛ إذا دُكّ أساسه انهار العدل وإنصاف المظلوم. الصدق في الحكم وإغاثة المظلوم، بغيابهما، يُظلم البريء ويطغى الظالم، ويأفل النور ليترك مكانه لديجور أبدي قاتم. ء

هذا الفتى سُجن ظلماً رغم براءته الصارخة. قاضٍ عاجز عن قول كلمة الحق، ينطق بكذب معتم فاقداً ذمته وكرامته. قاضٍ تحت التهديد والترهيب يحكم عليه بسجن مؤبد قاهر. أليس هذا واقعنا؟

تأبى « الفزعة » الوقوف، وتقذف بأمّ حُرمت أسرتها؛ ضحية تسمم أودى بحياة جنينها وزوجها. أُهينت الروح البشرية حتى تُهدر عبثاً. قد يترك الإنسان كنوز الدنيا وجوهرها ويتشبث بقشة نجاة هي قليل القليل في سبيل سعادته، فإذا ما سُلبت غدت الدنيا ظلماء قاهرة. بألم وحرقة ودموع حارة حارقة تبكي الأم فقدانها، وتوجه أصابع اللوم والاتهام للسلطات التي سمحت لمياه المجاري أن تخترق أنظمتنا الغذائية بطريقة غير مباشرة. ء

ثم على أنغام العود المربكة تدور الدوامة، وتبرز فتى شوّه وجهه ينعى بألم العمال الذين تُسلب صحتهم بغياب سبل الحماية وتُهضم حقوقهم ويُطالبون بالسكوت. أليس هذا القتل بعينه؟ بل هو قتل للروح وترك للجسد عائماً تائهاً حتى ننعته بالمجنون. هي حلقة تُسجن فيها الأجساد في انتظار من يحررها. فهل من مجيب؟

بدا لي هذا الرباعي في تحركه الدائري كإعصار هائج، بل هو سطح راكد يحمل زوبعة غاضبة تنتظر اللحظة التي تفتك فيها بمن حولها فلا ترحم أحداً. ء

كانت المسرحية مزيجاً من الكوميديا الهازئة الساخرة والتراجيديا المؤلمة القاهرة. كانت الأضواء مؤثرة؛ فدرجات الأصفر كانت باعثة للبهجة والألم في بعض المواقف، والأحمر للإحساس بالذنب والندم، دون أن ننسى درجات الأزرق التي أضفت نوعاً من البرودة والحزن. إلى جانب الأضواء، كان للموسيقى دور في توجيه مجرى النقد؛ فالأغاني ذات الصبغة الوطنية عبرت عن مقدار الألم الذي نحمله في أعماقنا تجاه الحال الذي غدونا فيه، جامع الغناء والرقص بين الجانب الغربي والشرقي، مما جعل العمل الفني موجهاً لمختلف الفئات. ء

الأزياء كانت عاكسة لطباع كل شخصية، مما مكّن من فهم معمق لمجرى الأحداث. أما بالنسبة للتوضيب الركحي، فقد كان حضور الممثلين بارزاً، وتوزيعهم متناسقاً متماسكاً، وربما ذو تأثير غير مباشر على المشاهدين: المستويات الثلاث، الجوقة، التقابل الدائم توحي بالتصادم بين عليّ ونبيل. ء

كانت مشاعري وعواطفي تنساق في انسياب بين خفة الكوميديا وحرقة التراجيديا. أن تشاهد ألم الواقع معروضاً أمامك مريح ومربك في الوقت ذاته؛ فأنت أمام الصورة القبيحة لمجتمع خبرته وأحببته. هزّت أوصالي قشعريرة في مختلف المواقف وامتزجت أحاسيسي. لكن ما كنت أوقن وجوده في داخلي هو الفخر بانتمائي للمعهد الوطني للعلوم التطبيقية والتكنولوجيا، حيث يمتزج الجد بالهزل، والإبداع بالحياد. فلا تستطيع إلا أن تشاهد العرض برضا وتشوق. ء

من خلال التناسق الواضح بين الممثلين والتقنيين، يمكنك أن توقن أن عملاً بمثل هذا الإتقان لا يكون إلا لقاح صداقة متينة تجمع بين أعضاء « تياترو ». لا يسعني إلا أن أسأل بحماسة وفضول: ماذا تجهزون للعرض القادم؟

Share your thoughts